Parker Hannifin’s Elvis Leka and Josh Coe detail how direct-to-chip liquid cooling, careful routing, low-restriction couplings and advanced monitoring and control can be combined to manage high heat loads while preserving rack density and system efficiency.

New AI data centres require more power and generate more heat; as a result, these new facilities need additional cooling. The irony is that AI server racks are significantly denser than standard compute racks to handle the increased power requirements, so there is less space for cooling systems. High-density data centres also have many servers packed into a limited area, which means compact cooling systems are critical to avoid consuming valuable floor space and to allow for maximum rack density and future expansion.

In addition, high-density AI servers create concentrated heat zones known as hotspots. Effectively managing heat created by hotspots requires placing cooling solutions directly next to them. Compact, industry-specific cooling systems deliver thermal management precisely where it’s needed, driving efficiency in the ecosystem and preventing localised temperature issues, which can cause premature failure of equipment.

The impact of AI

AI workloads require higher power density per rack, with some estimates suggesting they can be 4 to 100 times more than traditional data centres. A single ChatGPT query uses about 2.9 Wh compared to 0.3 Wh for a Google search. Training AI models requires even more power, with some racks consuming 80 kW or more, and newer chips possibly requiring up to 120 kW per rack.

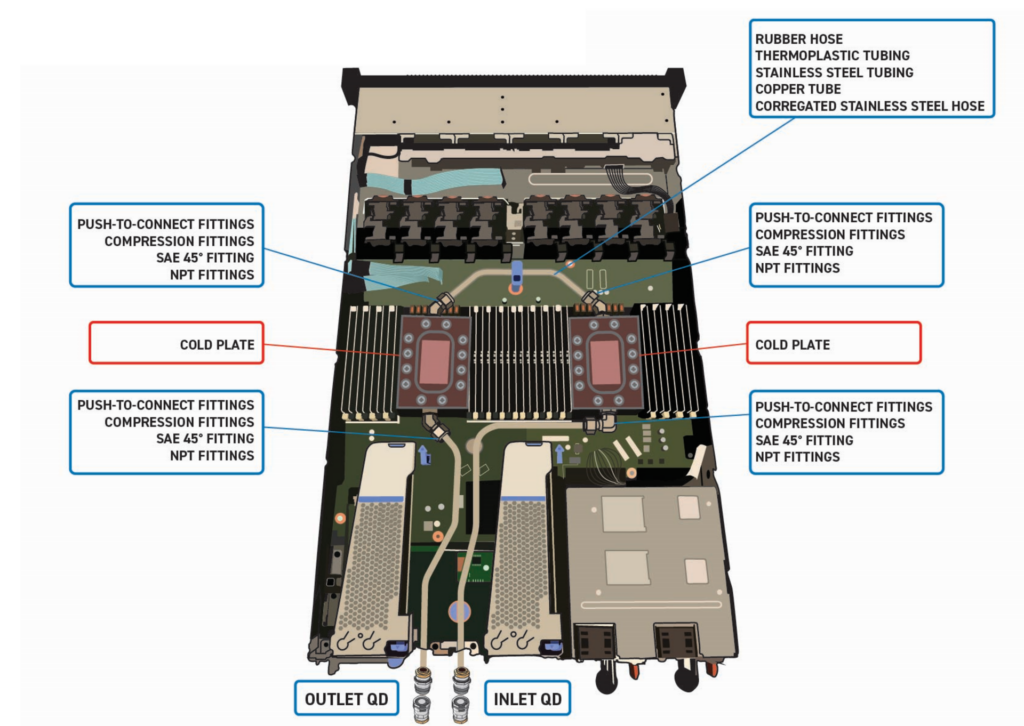

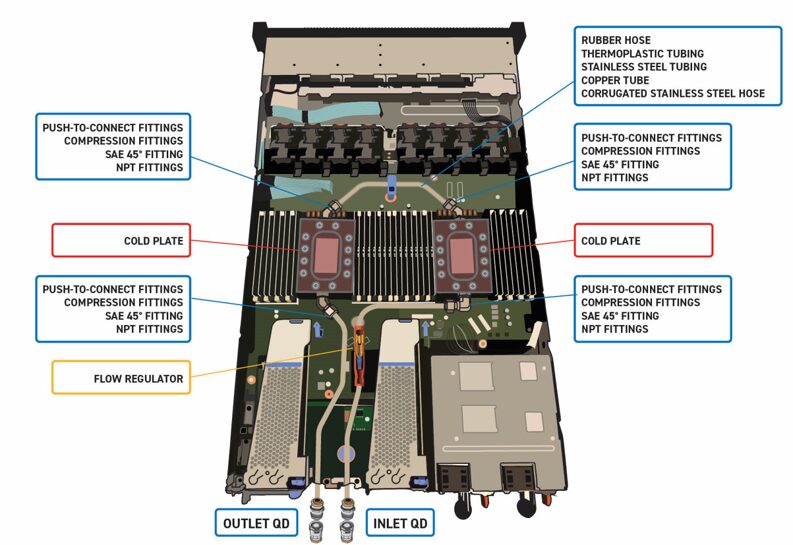

As the thermal design power (TDP) of the chips increases, space constraints arise from adding more advanced cooling systems. While cooling systems are essential for managing heat, the additional infrastructure required – including the cold plates, tubing, and coolant distribution units (CDUs) – can consume valuable space and complicate system designs.

Thermal management is critical for AI data centres due to their use of highly dense clusters of powerful chips (like GPUs) that generate significantly more heat than traditional servers, pushing traditional cooling systems to their limits. This increased heat generation requires more powerful, energy-intensive cooling solutions. The greater density of AI workloads can lead to thermal spikes that overwhelm existing capacity, risking hardware degradation, performance throttling, and costly downtime.

The evolution of today’s more efficient data centre cooling systems

To develop efficient cooling system designs, a solid knowledge of fluid transfer systems is required. While air-cooled systems previously dominated the industry for thermal management, power requirements have increased with newer chips that have increasingly higher TDP.

As a result, the industry is increasing investment in liquid cooling options, such as immersion cooling and two-phase cooling. Benefits of liquid cooling include more efficient heat transfer, lower cost and less environmental impact. Liquid cooling significantly reduces energy use, which reduces total operating expenses and creates a more sustainable data centre. In addition, there is a reduction in noise and the ability to extend hardware life.

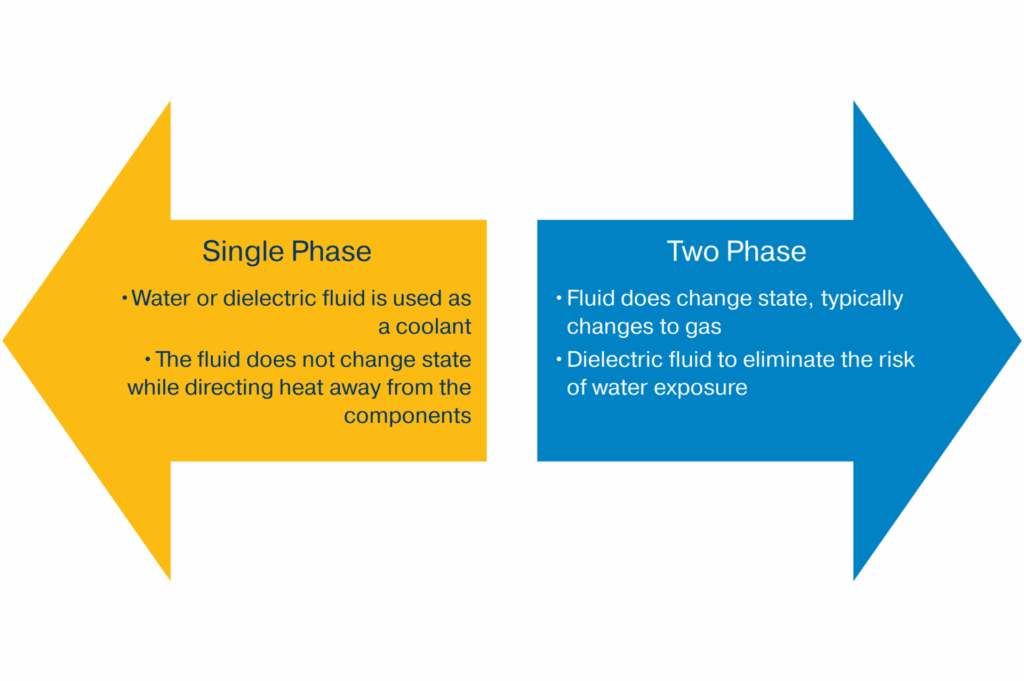

Direct-to-chip liquid cooling can be categorised into two main types: single-phase and two-phase. Both use a cold plate heat exchanger mounted directly onto the energy-dense components (CPU, GPU, etc.).

With single-phase cooling, a coolant such as water glycol (a mixture of water and propylene glycol) or de-ionised water with additives that inhibit biological growth and limit corrosion is used and circulated inside the cold plate by coolant distribution units (CDUs). The coolant absorbs heat as it passes through the cold plate heat exchanger which is in direct contact with the GPUs and CPUs to promote effective heat transfer. This process of absorption and direct cooling is also known as sensible heat transfer.

Although single-phase liquid cooling systems are sufficient for today’s data centres, they may struggle to meet the requirements of future generations of AI-rich data centres, which is why two-phase options are gaining popularity.

In two-phase cooling, heat absorption primarily occurs through latent heat during the phase change of the refrigerant. This process continuously cycles the refrigerant within a sealed, closed-loop system using a small pump to deliver just enough liquid refrigerant to the evaporator. Typically, a series of one or more cold plates is optimal to acquire the heat from the IT gear. The liquid refrigerant begins to boil and maintains a cool, uniform temperature on the surface of the chips. The two-phase refrigerant is then transferred to a heat exchanger where it rejects the heat to the facility cooling loop.

Two-phase systems are ideal for high-power electronics where heat loads have moved beyond what traditional air and water (single-phase) cooling systems can effectively manage. Direct-to-chip two-phase cooling is growing in the market due to its capability to transfer high heat and disperse latent heat created by electronic components with increased power densities. This highly efficient design simplifies plumbing and reduces the weight of the system, giving it an excellent thermal performance/cost ratio.

However, direct-to-chip pumped two-phase systems do have their drawbacks, including the fact that they often require a larger investment upfront and specialised training for maintenance technicians. There is also the technical challenge of designing a system that controls flow and pressure across cooling loops.

The need for more advanced monitoring and control systems

Newer two-phase liquid cooling systems require more sophisticated monitoring and control systems because of their efficiency-driven, yet sensitive, nature, which hinges on precise control of temperature, pressure, and flow to prevent overheating, leaks, and component failure. The process of changing from liquid to vapour to absorb heat is highly efficient but is sensitive to flow changes, which can cause issues like dry-out or vapour blockages if not properly managed. That’s why these advanced systems require the use of sensors and AI/ML-driven analytics to perform real-time condition monitoring, dynamic adjustments to offset workload fluctuations, and predictive maintenance.

Since efficiency is a priority when designing a cooling system, it is important to compute the total energy usage by looking at Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) at all levels (server blade level, IT rack level, and data centre facility levels). A PUE value of 1.0 indicates that all power is used by IT equipment, while a higher PUE indicates that more energy is being wasted on cooling and power delivery. Lowering PUE values across all levels helps improve overall energy efficiency and sustainability.

The facility PUE is the total energy used by the entire data centre (including cooling, lighting, and power delivery) divided by the energy used by the IT equipment. IT equipment PUE at the rack or server level measures the power used by the specific equipment against the total energy delivered to that equipment. To get an overall energy usage picture, you can multiply the PUE at each level by the energy consumption at that level, starting with the server blade and working your way up to the facility’s total energy consumption.

To calculate the blade PUE, divide the power used by the IT equipment on the blade by the power delivered to the blade. Then multiply the blade PUE by the total power consumed by the IT equipment on that blade to calculate the total blade energy usage. You can follow the same procedure to calculate total rack energy usage and total facility energy usage.

To maximise efficiency, it is important to evaluate the size requirements for all components in the cooling system. Maximising the efficiency of a two-phase liquid cooling system involves precisely sizing each component to match the thermal load, minimising energy consumption, and optimising heat transfer. Over-sizing components leads to wasted energy and higher costs, while under-sizing can cause performance issues or system failure.

Minimising pressure drop

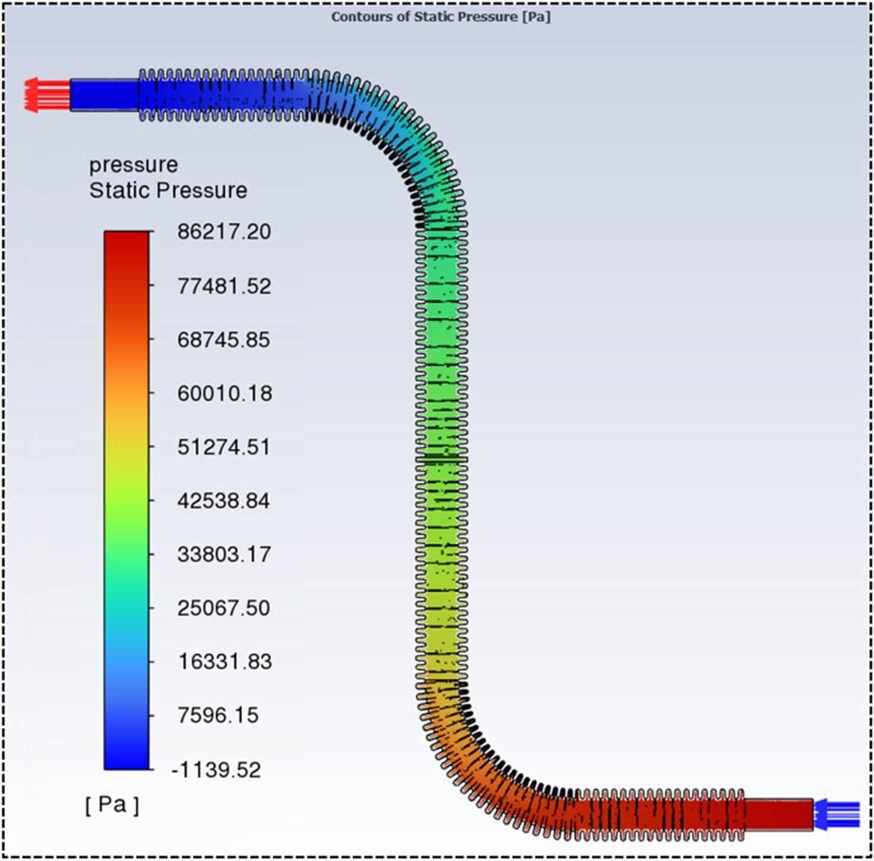

Pressure drop is the decrease in fluid pressure as it flows through a system. This decrease is caused by resistance from friction, pipe fittings, and obstructions. It is a crucial factor in system design, as it determines the energy required to move fluids and can affect performance if not accounted for.

Excessive pressure drop leads to reduced system efficiency, increased energy costs, and accelerated equipment wear. To overcome this loss, systems must use more energy, raising operational expenses and lowering productivity. When using refrigerant as the cooling media, pressure drop can cause the fluid to potentially vapourise, causing decreased mass flow. Furthermore, high pressure drops can cause equipment damage and premature failure. Pumps work harder and consume more power as a result of pressure drop.

Some of the more common sources of pressure drop in data centre liquid cooling systems include inefficient routings, restricted bore connections, hoses, fittings and cold plates, as well as internal obstructions such as deposits or dirt and flow restrictors. The total pressure drop is the sum of the pressure drops from all individual components in the cooling loop.

Looking at the potential impact of various components on total pressure drop, it’s easy to see how the accumulation of various factors can create substantial energy drain. Consider the following possible impacts:

- Hoses, tubing, and fittings – The internal design and connections of hoses, tubes, and fittings can create resistance to flow. Ensure all component materials are compatible with the coolant, operating temperatures, and pressures of the system to prevent corrosion and maintain structural integrity.

- Cold plates – The fluid must pass through the internal channels of the cold plates, which can cause a significant pressure drop depending on their design.

- Connectors – Quick-disconnects and other couplings are designed to be reliable and easy to use; however, the internal valve mechanism makes quick-disconnects one of the main contributors to pressure drop in a system. That’s why companies like Parker manufacture flat-face, dry-break couplings that feature high flow rates and low pressure drop.

- Hose and tubing routing – The overall layout and dimensions of the fluid transfer system contribute to the total pressure drop.

- Gasketing and seals – In some components, the gaskets can create a mechanical limit that results in a pressure drop.

- Manifold considerations – Properly designed manifolds ensure consistent flow, reduce pump load, and maintain cooling efficiency across the rack. Manifolds should be designed with parallel flow paths to distribute coolant evenly and reduce the overall pressure drop, ensuring all connected servers receive consistent flow.

Strategies for minimising pressure drop involve optimising the system’s design, component selection (including hose and tube sizing, as well as choosing the right material), and maintenance practices. Here are a few helpful tips to keep in mind:

- Use parallel flow configuration – Arranging the cold plates or cooling modules in a parallel circuit distributes the fluid into multiple paths, significantly reducing the pressure drop compared to a series configuration. This design also prevents downstream components from being preheated by the upstream fluid.

- Minimise bends and shorten pipe length – Excessive 90-degree bends, twists, and long pipe runs create turbulence and friction, leading to significant pressure loss. Design piping layouts to be as compact and straight as possible.

- Increase hose and tube diameter – Larger diameter hoses and tubing offer less resistance to fluid flow, reducing friction and pressure drop. However, this must be balanced with space and cost constraints.

- Create smooth interior surfaces – Rough internal pipe surfaces increase friction. Using pipes with polished, smooth interior finishes minimises drag on the fluid.

- Use low-viscosity coolant – The viscosity of the cooling fluid directly affects friction. Using a fluid with a lower viscosity will reduce the resistance to flow and the resulting pressure drop.

- Specify low-restriction fittings and quick-disconnects – Generic quick-disconnects can cause unnecessary pressure loss. Instead, use specialised, high flow quick-disconnect fittings that feature advanced internal designs and optimised flow paths to minimise restriction.

- Reduce components in the flow path – Every valve, flow meter, and coupling adds resistance. Minimise the number of these components to create a more streamlined flow path.

A well-designed system with low pressure drop prevents localised high-pressure areas that can lead to leaks or uneven cooling. This is especially critical for high-density servers, where one component failing could impact others. In addition, reduced pressure drop ensures the coolant can be distributed efficiently to all servers. This enables the cooling system to effectively manage the heat generated by high-performance computing (HPC) and AI workloads. A reliable system with fewer pressure-related issues requires less frequent maintenance, leading to lower system operation costs.

Conclusion

High-density AI data centres require more innovative cooling strategies because of their significantly higher power requirements. At the same time, these newer cooling solutions must be compact in nature due to higher rack and chip densities and the addition of cold plates.

Over the years, cooling technologies have evolved to better meet increased energy demands – moving from air cooling to single-phase liquid cooling to single-phase and air hybrid cooling to two-phase liquid cooling strategies.

Fluid performance is improved with constant flow rates, but pressure drops threaten a system’s ability to maintain a consistent flow. Design configuration and material selection, along with the type of connections and sealants chosen, all impact pressure drop. There are several proven-successful strategies for reducing pressure drop which are necessary to increase energy efficiency and extend the life of system components.

Getting all the additional cooling components, along with the servers’ power and data cabling, to fit in the same, or an even smaller, footprint has become exponentially more complex. That’s why precise planning is necessary when designing today’s latest cooling systems. System-built solutions utilising compact designs and optimisation of flow rates and routings inevitably lead to improved component lifespans and reduced overall system operating costs.