The COVID-19 outbreak is causing panic around the world as supermarkets run out of toilet paper and dried pasta, while governments put entire countries in lockdown. One of the issues surrounding this new strain of coronavirus is the fact that there is no cure, however, Nvidia wants everyone with spare GPU power to lend a helping hand in creating one.

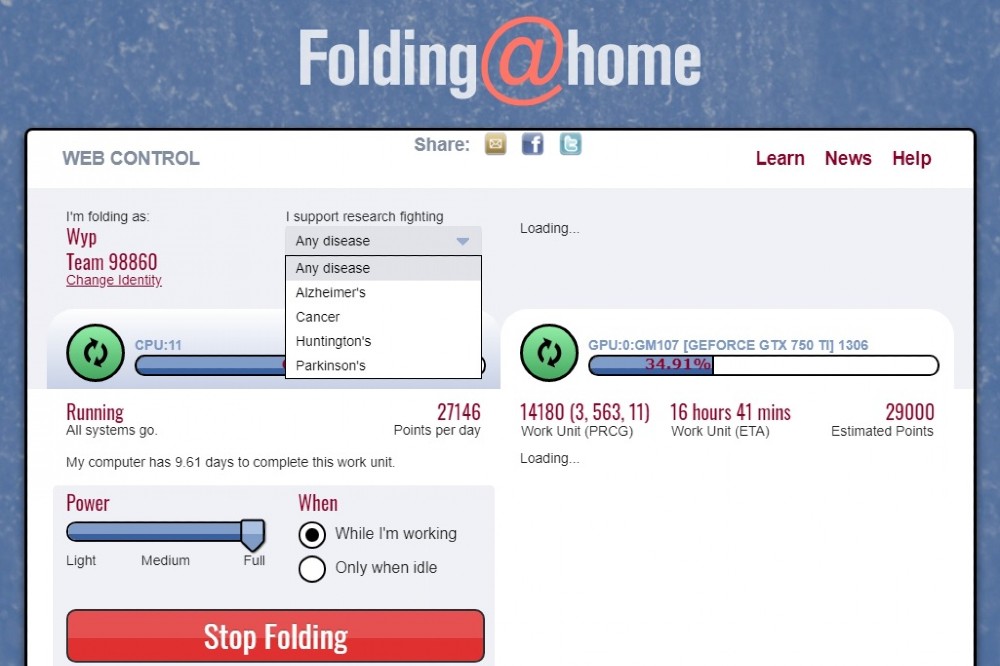

On its social media channels, Nvidia has been advertising a piece of software called ‘Folding@Home’, which can be installed on any Linux, Windows or Mac computer. Essentially the software leverages your GPU or CPU power to contribute to a distributed supercomputer. This supercomputer can then get to work finding a cure for COVID-19.

Folding@Home is nothing new, the brain child of researchers at Stanford University, the software has actually been available for some time, offering users a way to donate GPU and CPU power towards fighting diseases. The software was recently updated, however, to combat the coronavirus known as COVID-19.

Stanford University hopes that the Folding@Home software will soon reach one million contributors, which will give it a lot of processing power. In a press release, Folding@Home explains how it can actually help:

Proteins are molecular machines that perform many functions we associate with life. They sense the environment (e.g. in taste and smell), perform work (e.g. muscle contraction and breaking down food), and play structural roles (e.g. your hair). They are made of a linear chain of chemicals called amino acids that, in many cases, spontaneously “fold” into compact, functional structures. Much like any other machine, it’s how a protein’s components are arranged and move that determine the protein’s function. In this case, the components are atoms.

Viruses also have proteins that they use to suppress our immune systems and reproduce themselves.

To help tackle coronavirus, we want to understand how these viral proteins work and how we can design therapeutics to stop them.

There are many experimental methods for determining protein structures. While extremely powerful, they only reveal a single snapshot of a protein’s usual shape. But proteins have lots of moving parts, so we really want to see the protein in action. The structures we can’t see experimentally may be the key to discovering a new therapeutic.

Using football as an analogy for the experimental situation, it’s as if you could only see the players lined up for the snap (the single arrangement the players spend the most time in) and were blind to the rest of the game.

Seeing a single structure of a protein (left) is like seeing players lined up for the snap in football. Important information, but a lot missing too. The protein structure shows a sphere for each atom (blue) and red arrows highlighting the one drug binding site in this protein.

Our specialty is in using computer simulations to understand proteins’ moving parts. Watching how the atoms in a protein move relative to one another is important because it captures valuable information that is inaccessible by any other means.

Taking the experimental structures as starting points, we can simulate how all the atoms in the protein move, effectively filling in the rest of the game that experiments miss.

A movie capturing how the protein shown before moves is like getting to watch the whole football game. In this case, we see a pocket form that was absent in the experimental structure.

Doing so can reveal new therapeutic opportunities. For example, in our recent paper, we simulated a protein from Ebola virus that is typically considered ‘undruggable’ because the snapshots from experiments don’t have obvious druggable sites. But, our simulations uncovered an alternative structure that does have a druggable site. Importantly, we then performed experiments that confirmed our computational prediction, and are now searching for drugs that bind this newly discovered binding site.

Our simulations captured a motion that creates a potentially druggable site in the Ebola protein. Instead of showing spheres for each atom, this cartoon shows a ribbon tracing the linear chain of amino acids (chemicals) the protein is made of.

We want to do the same thing with coronavirus, and you can help! In fact, there are a number of ways you can help, and they’re not mutually exclusive.

- Downloading Folding@home and helping us run simulations is the primary way to contribute. These calculations are enormous and every little bit helps! Each simulation you run is like buying a lottery ticket. The more tickets we buy, the better our chances of hitting the jackpot. Usually, your computer will never be idle, but we’ve had such an enthusiastic response to our COVID-19 work that you will see some intermittent downtime as we sprint to setup more simulations. Please be patient with us! There is a lot of valuable science to be done, and we’re getting it running as quickly as we can.

- If you don’t have computers to contribute or are feeling particularly generous, you can also make donations through Washington University in St. Louis. These funds are used for a number of purposes, including: 1) supporting our software engineering and server-side hardware (particularly important right now as we scale up rapidly!) and 2) buying compounds to test experimentally based on insight from our simulations.

- Of course, please take precautions to help prevent the spread of the virus by washing your hands, social distancing, etc. Doing so helps sustain the medical system and buys scientists time to hunt for therapies.